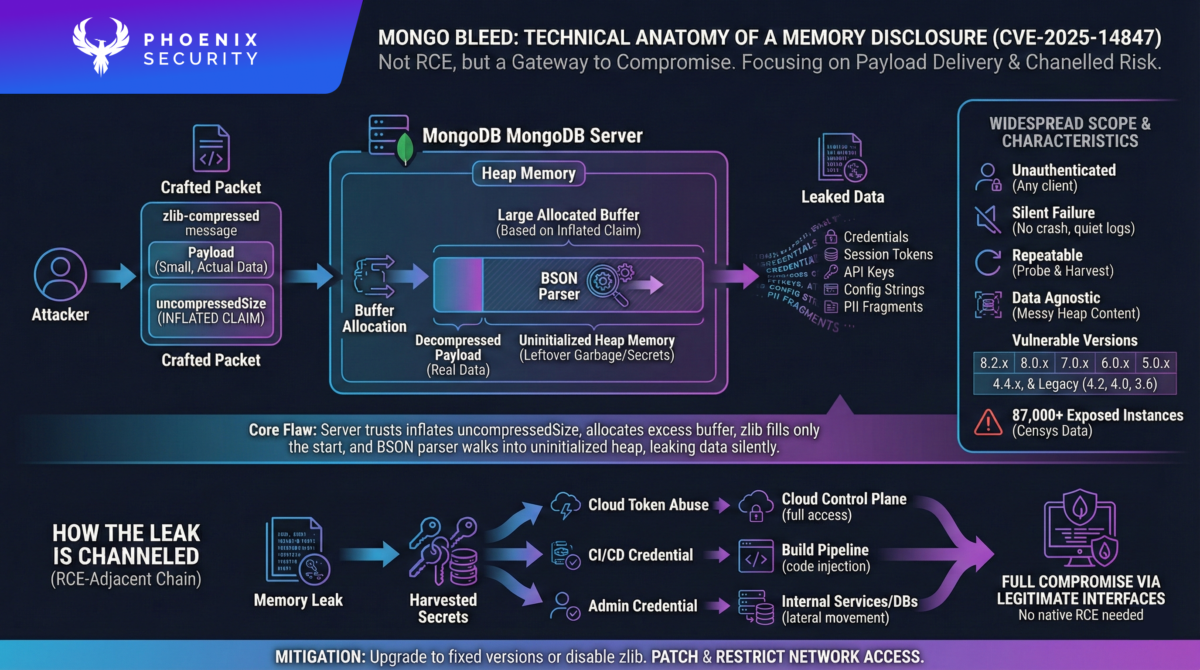

CVE-2025-14847 exposes MongoDB servers to unauthenticated memory leaks at internet scale, with over 87,000 internet-facing MongoDB instances observed. Note: this is not an RCE but a memory leak; nonetheless, RCE could likely follow.

TL;DR for Engineering Teams

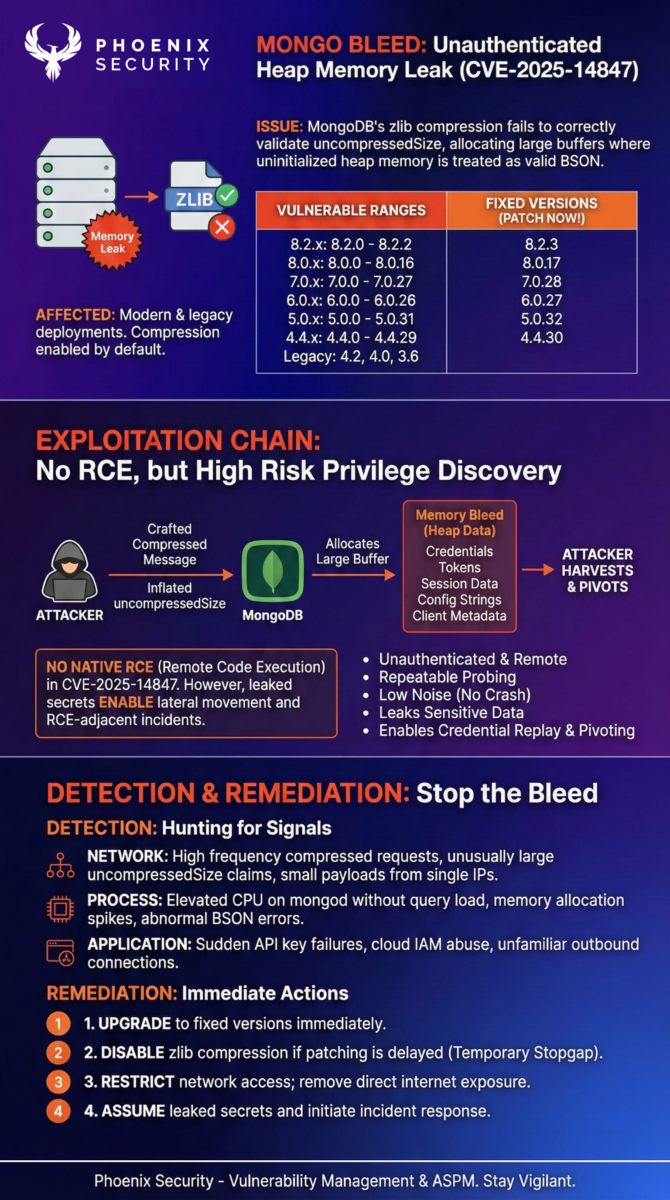

- What broke: MongoDB’s zlib decompression mishandles buffer lengths.

- Danger: Not an RCE but a memory leak; nonetheless, it could be chained with other popular RCEs such as React2Shell.

- What leaks: Uninitialized heap memory from the database process.

- Auth required: None.

- Exposure: Over 87,000 internet-facing MongoDB instances observed.

- Why it hurts: Memory can contain credentials, tokens, PII, and internal paths.

- Fix: Upgrade immediately or disable zlib compression.

- Reality check: Public PoC exists. Scanning is trivial. This will be abused.

Contents

ToggleAffected Versions

| Package | Vulnerable Versions | Fixed Versions | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MongoDB Server | 8.2.0 – 8.2.2 | 8.2.3 | |

| MongoDB Server | 8.0.0 – 8.0.16 | 8.0.17 | |

| MongoDB Server | 7.0.0 – 7.0.27 | 7.0.28 | |

| MongoDB Server | 6.0.0 – 6.0.26 | 6.0.27 | |

| MongoDB Server | 5.0.0 – 5.0.31 | 5.0.32 | |

| MongoDB Server | 4.4.0 – 4.4.29 | 4.4.30 | |

| MongoDB Server | All 4.2.x | N/A | End of Life |

| MongoDB Server | All 4.0.x | N/A | End of Life |

| MongoDB Server | All 3.6.x | N/A | End of Life |

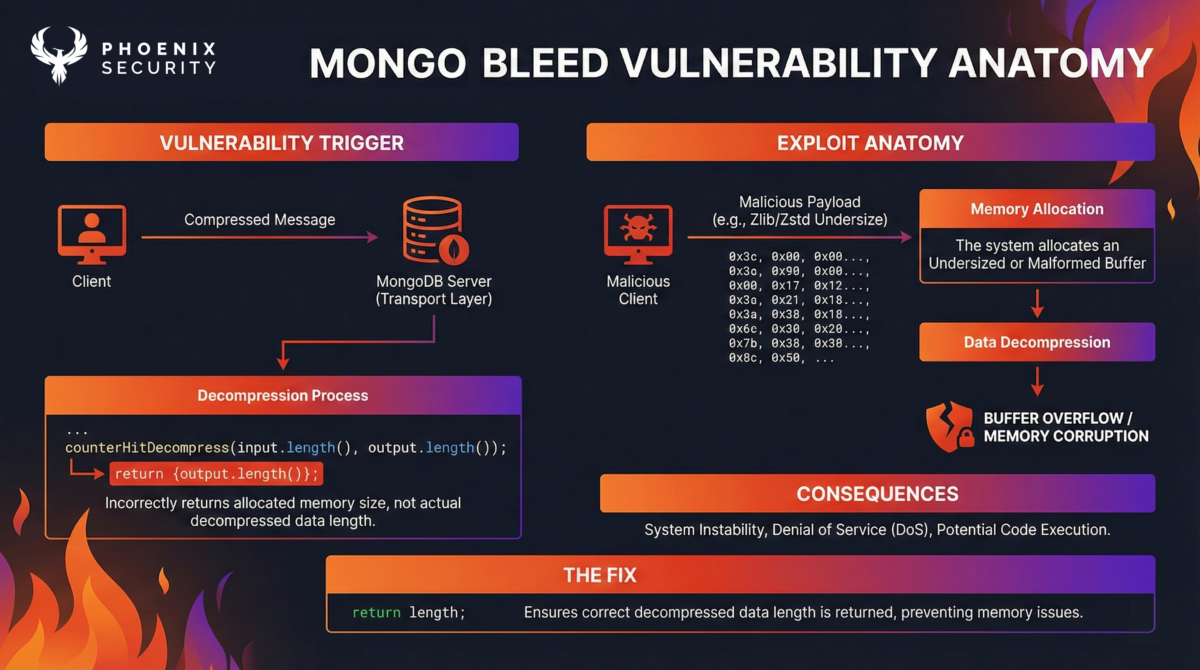

What Is MongoBleed?

MongoDB is a popular database and has a memory access issue (MongoBleed).

MongoDB supports network message compression. When a client sends a compressed message, it includes a field called uncompressedSize. MongoDB allocates a buffer of that size before passing the payload to zlib.

Here’s the failure mode:

- Attacker sends a crafted message with an inflated uncompressedSize.

- MongoDB allocates a large heap buffer.

- zlib only decompresses the real payload into the start of that buffer.

- The remaining buffer space stays uninitialized.

- MongoDB treats the entire buffer as valid BSON.

- BSON parsing walks into leftover heap memory.

At that point, the database starts leaking whatever was in memory previously.

The challenge is: there is no crash. No auth failure. Just data bleeding out.

The resemblance to Heartbleed is not accidental. Same class of bug. Same trust failure. Same outcome. The difference is that there is no known RCE attached to this yet…

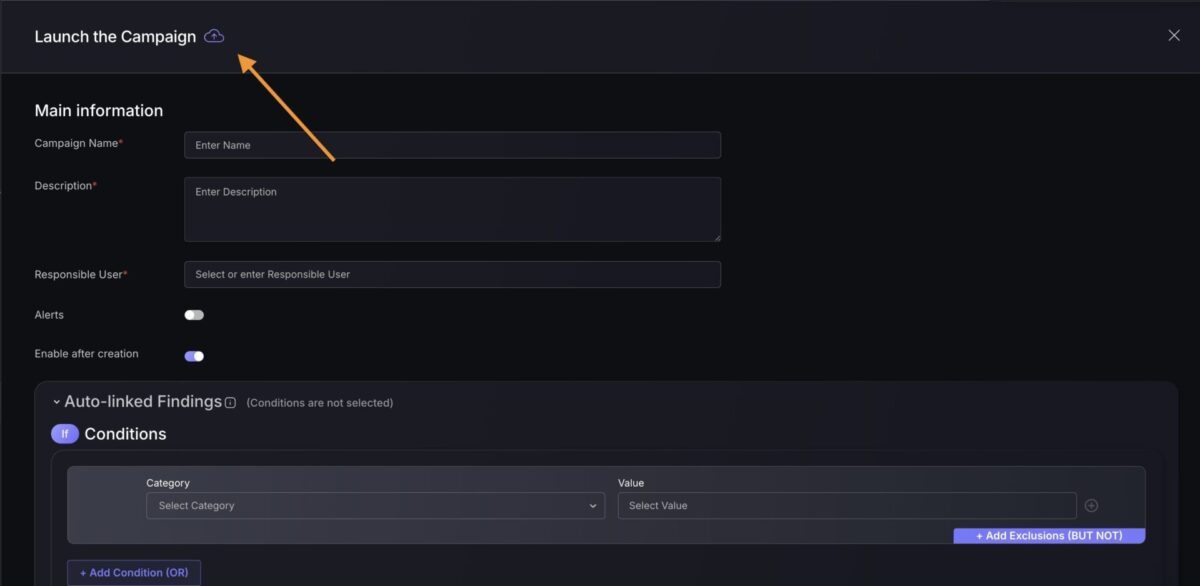

Campaign to identify if your libraries are affected by the MongoBleed CVE-2025-14847 in Phoenix Security

Leverage the Phoenix Security SCA Scanner and the container Docker image scanner to identify the vulnerability blast radius

Scan with the Git automatic scanner or pull the repo individually (finding can be synced to Phoenix using –enable-phoenix and modifying the config: https://github.com/Security-Phoenix-demo/mongobleed-exploit-CVE-2025-14847/tree/main

Leverage Phoenix Security Filters and the campaign method to update/ retrieve the new vulnerabilities, or import this file:

Check the libraries not affected in SBOM screen to detect mongobleed (search the following libraries)

- mongodb

- mongodb client

Check Vulnerability Screen in Phoenix Security

POC and Exploit for CVE-2025-14847 (MongoBleed)

A working proof of concept for CVE-2025-14847, commonly referred to as MongoBleed, is publicly available and demonstrates how trivial exploitation is once network access to a vulnerable MongoDB instance exists. The PoC, published by Joe Desimone, implements the exact compression-size mismatch condition that triggers uninitialized-heap disclosure by sending syntactically valid zlib-compressed messages with attacker-controlled uncompressed-length fields. The exploit requires no authentication, no malformed compression streams, and no timing conditions.

Check out the original PoC here and here

Check out the exploit below and the lab to test here:

The underlying mechanics and exploitation flow were first detailed in Kevin Beaumont’s technical analysis, which walks through the memory disclosure behavior and validates the issue against real MongoDB deployments. In addition to the original PoC, test harnesses and scanning tooling are available to reproduce the issue locally, assess exposed services, and validate vulnerable container images, including Docker-based environments. The availability of ready-to-run exploit code materially lowers the effort required to weaponize this vulnerability and increases the likelihood of opportunistic scanning against exposed MongoDB instances.

Link – incident write-up and PoC testing notes.

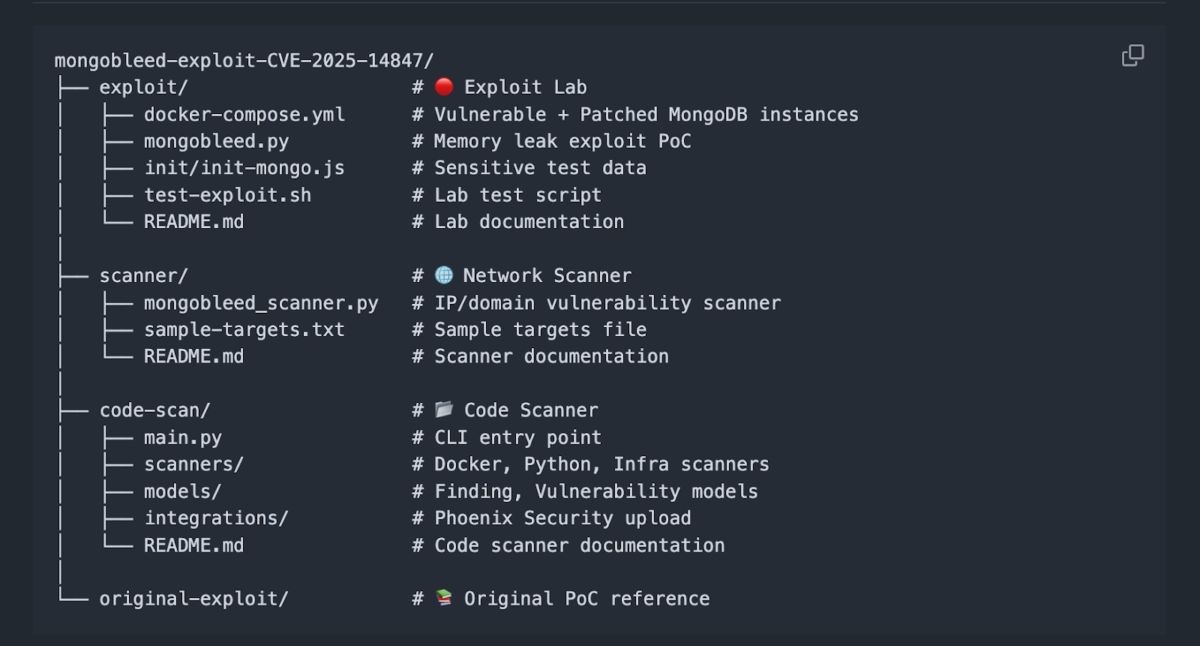

Exploit Lab, Network Scanner, and Code Scanner Tooling

Phoenix Security clients can already verify results with SCA, the container registry scanner, and the external scanner for internet-exposed systems.

To support validation, detection, and remediation workflows, Phoenix Security has released a full MongoBleed test suite that combines an exploit lab, a network scanner, and a code scanner in a single repository.

You can access the repo and run the scanners from here.

The exploit lab provides a controlled Docker-based environment with both vulnerable and patched MongoDB instances, allowing teams to safely reproduce the memory disclosure behavior and verify the effectiveness of upgrades by observing live heap leakage versus clean rejection paths.

The network scanner enables rapid identification of exposed and vulnerable MongoDB services across individual hosts, CIDR ranges, or target lists, using the same compression mismatch logic as the PoC to confirm reachability and exploitability rather than relying on version strings alone.

The code scanner extends this coverage into build and supply chain workflows by inspecting repositories, Dockerfiles, and infrastructure definitions to detect vulnerable MongoDB versions before deployment, with optional direct upload into Phoenix Security for attribution, prioritization, and tracking.

https://github.com/Security-Phoenix-demo/mongobleed-exploit-CVE-2025-14847

Root Cause and Technical Details

CVE-2025-14847 (MongoBleed) is caused by an incorrect propagation of decompression length semantics in MongoDB’s network transport layer when processing compressed wire-protocol messages.

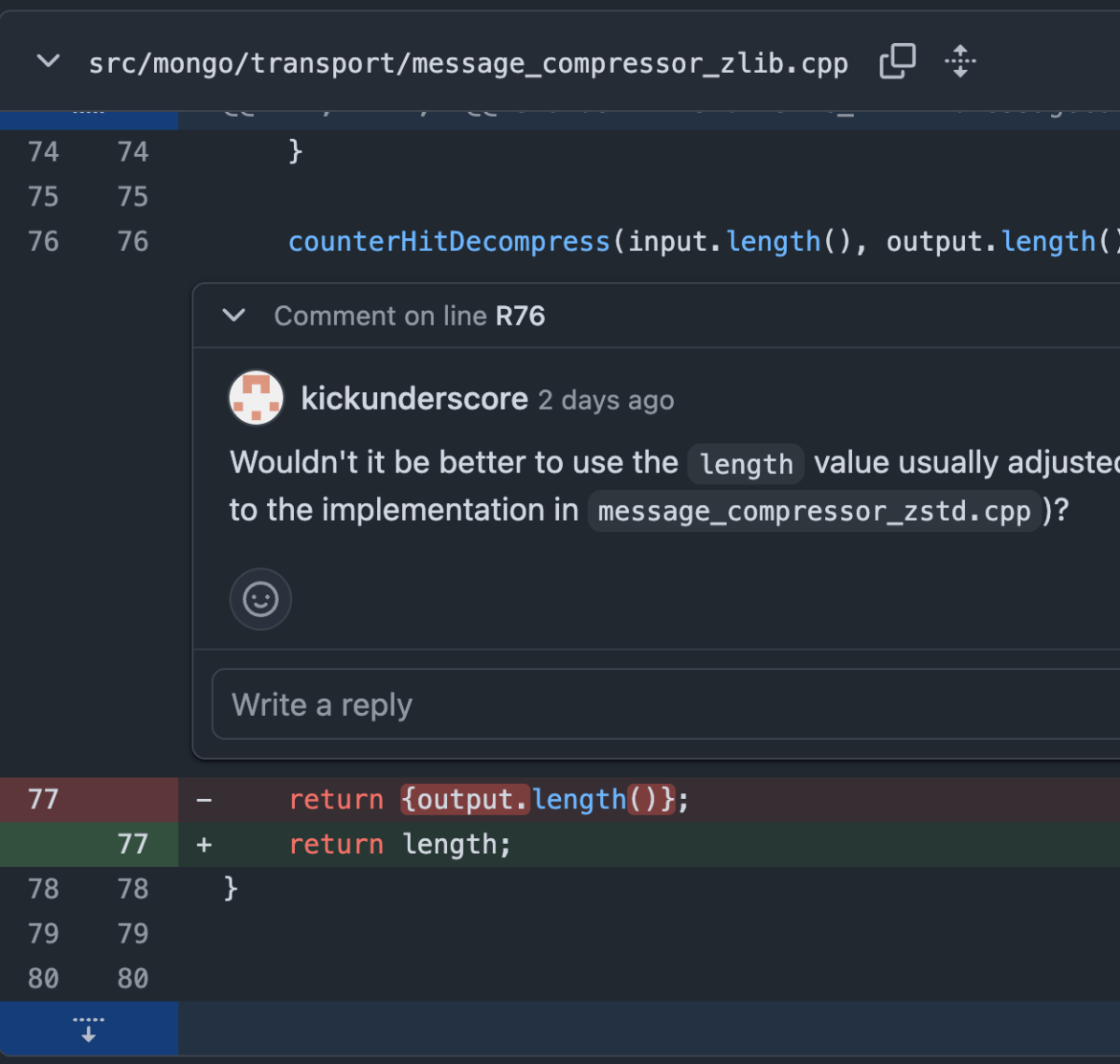

The vulnerability resides in MongoDB’s zlib message compression implementation, specifically in:

src/mongo/transport/message_compressor_zlib.cpp

When a client negotiates zlib compression and submits a compressed message, MongoDB allocates an output buffer based on the declared uncompressed size provided in the message metadata. The server then invokes ::uncompress() to inflate the payload into this buffer.

In the vulnerable implementation, the decompression routine returns output.length(), which corresponds to the size of the allocated output buffer, rather than the number of bytes actually written by the decompressor. As a result, MongoDB treats the entire buffer as valid decompressed data, even though only a portion of it contains legitimate payload.

This mismatch allows subsequent BSON parsing logic to read beyond the true decompression boundary and into uninitialized heap memory, leading to unauthenticated memory disclosure.

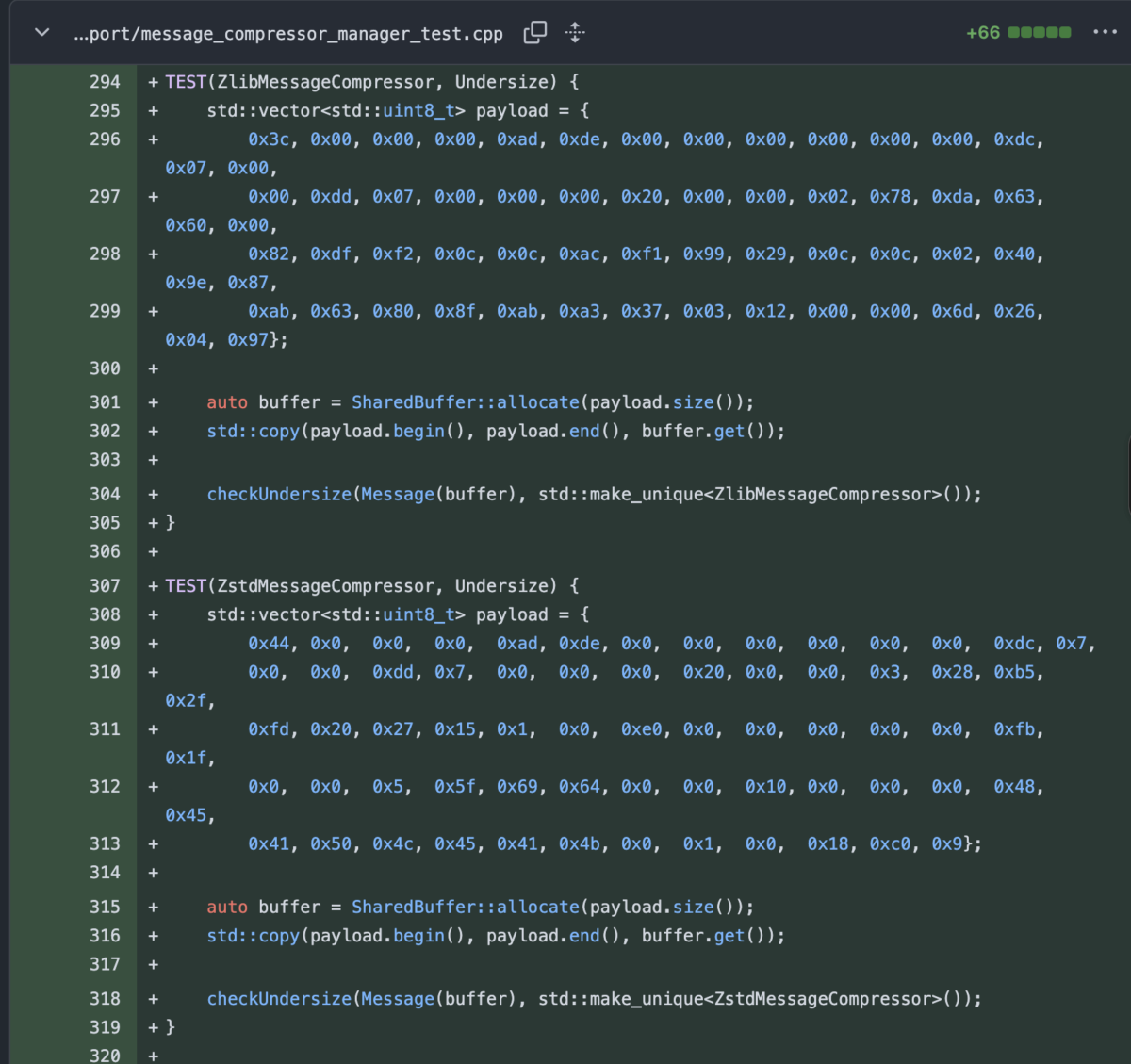

The issue was fixed by returning the actual decompressed byte count instead of the allocated buffer length, as shown in MongoDB’s official patch:

MongoDB fix commit:

https://github.com/mongodb/mongo/commit/505b660a14698bd2b5233bd94da3917b585c5728

If an attacker supplies a syntactically valid compressed message whose declared uncompressed size exceeds the real decompressed length, MongoDB treats the entire allocated buffer as valid decompressed data. Subsequent message parsing and BSON handling logic consume memory beyond the true decompression boundary, resulting in the exposure of uninitialized heap memory.

This condition is reachable without authentication and does not require malformed compression streams or memory corruption primitives. The exploit relies solely on a size mismatch between attacker-controlled metadata and the actual decompression output, combined with the incorrect return of allocated buffer length. The vulnerability is reliably triggered after compression negotiation and prior to authentication checks, making it reachable by any network client.

The issue was remediated by modifying the decompression path to return the actual decompressed byte count (return length;) instead of the allocated buffer size. Additional regression tests were introduced in message_compressor_manager_test.cpp to explicitly detect and reject undersized decompression results, ensuring that future mismatches between declared and real decompressed sizes result in a controlled error (ErrorCodes::BadValue) rather than memory disclosure.

src/mongo/transport/message_compressor_zlib.cpp

The fix replaces return {output.length()}; with return length;, ensuring that only the true decompressed byte count is propagated, preventing BSON parsing from walking into uninitialized memory.

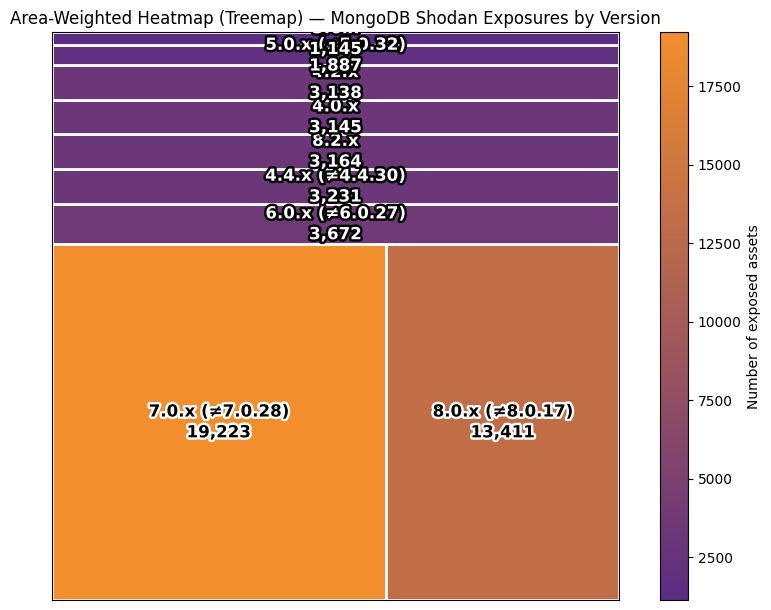

How Widespread Is CVE-2025-14847 (MongoBleed)?

MongoDB is one of the most widely deployed database platforms on the internet, and its exposure footprint directly amplifies the risk posed by MongoBleed.

We are looking at 213,490 potentially vulnerable systems on Shodan.

Current Shodan telemetry identifies 213,490 publicly reachable MongoDB instances, many of which advertise versions that fall squarely within the vulnerable ranges for CVE-2025-14847.

Those figures were captured on December 29, 2025.

| Version | Number of assets | Shodan query |

| All versions (baseline) | 213,490 | product:”MongoDB” port:27017 |

| 8.2.x | 3,164 | product:”MongoDB” port:27017 “8.2.” |

| 8.0.x (minus 8.0.17) | 13,411 | product:”MongoDB” port:27017 “8.0.” -“8.0.17” |

| 7.0.x (minus 7.0.28) | 19,223 | product:”MongoDB” port:27017 “7.0.” -“7.0.28” |

| 6.0.x (minus 6.0.27) | 3,672 | product:”MongoDB” port:27017 “6.0.” -“6.0.27” |

| 5.0.x (minus 5.0.32) | 1,887 | product:”MongoDB” port:27017 “5.0.” -“5.0.32” |

| 4.4.x (minus 4.4.30) | 3,231 | product:”MongoDB” port:27017 “4.4.” -“4.4.30” |

| 4.2.x | 3,138 | product:”MongoDB” port:27017 “4.2.” |

| 4.0.x | 3,145 | product:”MongoDB” port:27017 “4.0.” |

| 3.6.x | 1,145 | product:”MongoDB” port:27017 “3.6.” |

Distribution of various MongoDB versions.

The distribution spans cloud providers, managed hosting environments, and self-hosted deployments, with a heavy concentration on the default MongoDB port 27017, indicating direct internet exposure rather than controlled access through application tiers. The presence of affected versions across multiple major release branches, including long-lived production deployments, confirms that MongoBleed is potentially another Heartbleed-scale vulnerability.

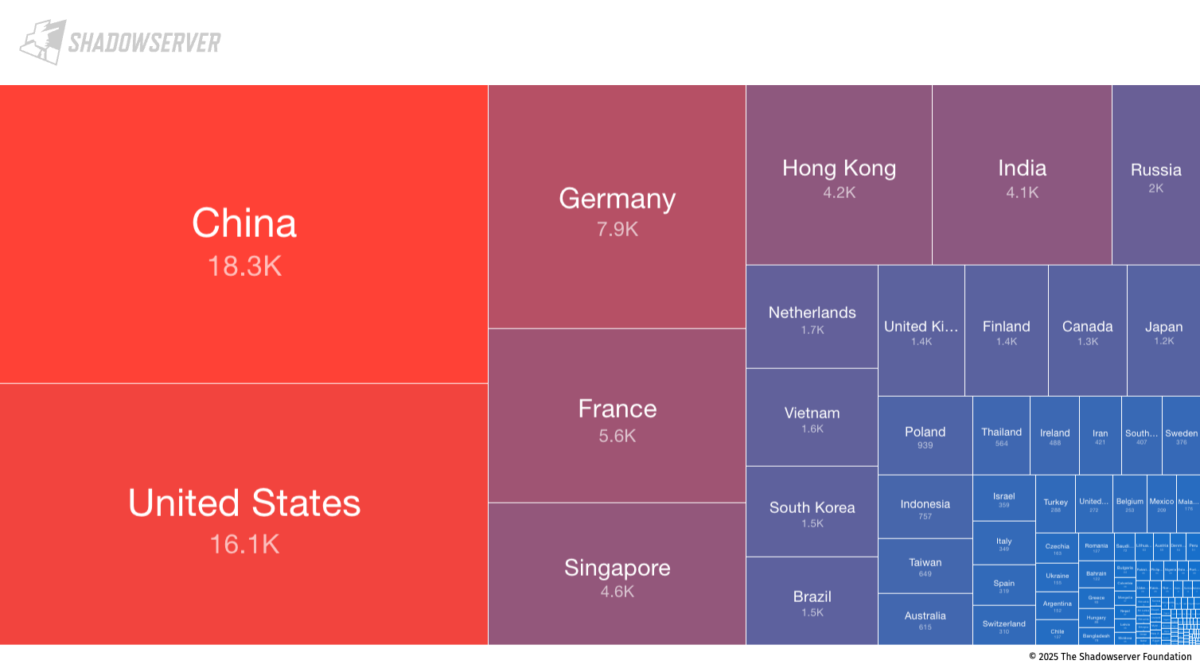

Below the number of Vulnerable attacks detected by shadowserver (details here)

Considering the low level of effort required to exploit this vulnerability, spray-and-pray opportunistic scanning significantly increases the likelihood of credential leakage, lateral movement, and downstream compromise.

Core behaviors

This vulnerability has a few traits that should make every security team uncomfortable:

- Unauthenticated. Any network client can trigger it. No user. No password. No role.

- Remote and repeatable. Attackers can probe memory offsets repeatedly and harvest fragments over time.

- Low noise. No malformed packets. No obvious crashes. Logs stay quiet.

- Data agnostic. Heap memory is messy. That’s the point. It often contains:

- Cleartext credentials

- Session tokens

- WiredTiger config strings

- File paths

- Container metadata

- Client IPs and connection details

- Recently processed documents

- Cleartext credentials

There is already PoC output showing real system and runtime artifacts

How to detect if you are affected by CVE-2025-14847

There is no native RCE in CVE-2025-14847.

It is a memory disclosure vulnerability, not code execution.

That said, below is a list of elements to hunt for—signals that can turn this leak into an RCE-adjacent incident.

How the security team should look for evidence of CVE-2025-1484747

MongoBleed enables:

- unauthenticated heap memory reads

- repeatable probing

- no crash

- no authentication trail

Note: this is not an RCE, so an attacker cannot directly execute code via the bug itself.

Attackers can:

- extract secrets

- extract credentials

- extract tokens

- extract internal topology

- pivot to other execution paths

1. Network-level indicators of exploitation attempts

What to look for

MongoBleed exploitation requires compressed MongoDB wire protocol messages with abnormal size claims.

Look for:

- inbound traffic to port 27017

- zlib-compressed messages

- repeated requests with:

- unusually large uncompressedSize

- small actual payloads

- unusually large uncompressedSize

- high request frequency from a single IP without authentication attempts

Practical detection ideas

- Enable packet capture or deep inspection on MongoDB traffic

- Alert on:

- repeated compressed requests

- malformed or oversized BSON messages

- high entropy traffic bursts without follow-on queries

- repeated compressed requests

2. MongoDB process behavior anomalies

Heap disclosure abuse leaves operational signals

Attackers running tools like MongoBleed do this iteratively.

Watch for:

- elevated CPU usage on mongod without query load

- repeated short-lived connections

- spikes in memory allocation without query execution

- abnormal BSON parsing errors or warnings

Even though MongoDB doesn’t log the leak, parsing garbage memory costs cycles.

If you see resource usage without workload justification, investigate.

3. Indicators that memory leakage has already enabled lateral movement

This is where RCE risk actually appears.

Check for credential abuse

MongoBleed leaks:

- database credentials

- SCRAM material

- internal service usernames

- sometimes cloud tokens in memory

Look for:

- new MongoDB users

- unexpected role changes

- auth attempts from unfamiliar IPs

- access to admin commands that were never used before

4. Application-layer fallout (most important)

MongoDB rarely lives alone. If attackers harvest secrets from memory, the application using MongoDB is now at risk.

Hunt for:

- sudden API key rotation failures

- cloud IAM token abuse

- service-to-service auth failures

- new outbound connections from app containers or hosts

This is where real RCE happens:

- attacker uses leaked secrets

- authenticates to CI/CD, cloud, or admin APIs

- executes code through legitimate interfaces

5. File system and process indicators on the host

MongoBleed itself does not drop files.

If you see:

- new binaries

- new cron jobs

- shell access

- unexpected child processes from mongod

You are past the vulnerability phase and into post-exploitation.

At that point:

- assume secrets were leaked

- assume memory disclosure was the enabler

- treat it as a full incident

6. Why RCE chaining is realistic here

Attackers don’t need shellcode when:

- MongoDB runs next to app runtimes

- containers share hosts

- memory holds environment variables

- tokens grant access to orchestration APIs

A leaked Kubernetes token is better than RCE.

A leaked CI token is better than RCE.

A leaked cloud role is persistent RCE.

MongoBleed is a privilege discovery bug, not a crash exploit.

Determine if you’re affected

Start with the basics:

- Check version

db.version() - Check compression settings

If zlib is enabled in networkMessageCompressors, you are exposed. - Check exposure

If port 27017 is reachable beyond a trusted network boundary, assume hostile traffic.

Check reality.

Censys data shows 87,000+* MongoDB instances exposed to the public internet.

* Please note: different internet scanners (e.g., Shodan vs. Censys) report different totals depending on methodology, filtering, and capture time.

If you think yours is private, verify. Don’t assume.

Temporary protections

If you cannot upgrade immediately, you still have options.

- Disable zlib compression

- Remove zlib from networkMessageCompressors

- Use snappy or zstd instead

- Or disable compression entirely

- Remove zlib from networkMessageCompressors

- Restrict network access

- Lock MongoDB behind private networks

- Enforce IP allowlists

- Remove direct internet exposure

- Lock MongoDB behind private networks

These are stopgaps, not fixes. The bug lives in the server.

How a threat actor could use this vulnerability

This is not a smash-and-grab exploit. It’s quieter and more dangerous.

A realistic attack chain looks like this:

- Scan

Identify exposed MongoDB servers with compression enabled. - Probe

Send crafted compressed messages to read heap fragments. - Harvest

Collect leaked memory over thousands of requests. - Extract value

- Credentials reused elsewhere

- Session material

- Internal topology

- Application secrets

- PII fragments

- Credentials reused elsewhere

- Pivot

Use leaked data to access applications, cloud resources, or internal services.

Because the heap changes constantly, attackers can keep sampling until something useful appears. This favors patient actors and automated tooling.

The PoC already supports scanning offsets up to 50,000 bytes and dumping raw memory to disk.

There is also a screenshot circulating with the PoC showing leaked system memory and runtime stats, which underscores how trivial reproduction is.

Why this one matters

MongoDB is everywhere.

Web apps. SaaS backends. Analytics stacks. Kubernetes workloads. Cloud-native services.

Compression is enabled by default. Authentication is often misconfigured. Internet exposure is depressingly common.

MongoBleed does not break crypto. It breaks trust.

The database assumes the client is honest about lengths. Attackers live for that assumption.

From an application security and DevSecOps perspective, this is a reminder that:

- Databases are part of your attack surface.

- Infrastructure bugs leak application secrets.

- Vulnerability management must include reachability and exposure, not just CVSS.

Patch this. Then ask why it was reachable in the first place.

Discovery and disclosure timeline

- Discovery: Identified by OX Security during protocol-level analysis.

- Disclosure: December 19, 2025.

- CVSS: 7.5 (arguably conservative given unauthenticated data exposure).

- PoC: Publicly released by Joe Desimone on GitHub under the name MongoBleed.

- Status: No public reports of mass exploitation yet. That window is closing fast.

Once a PoC exists, exploitation becomes a timing problem, not a skill problem.

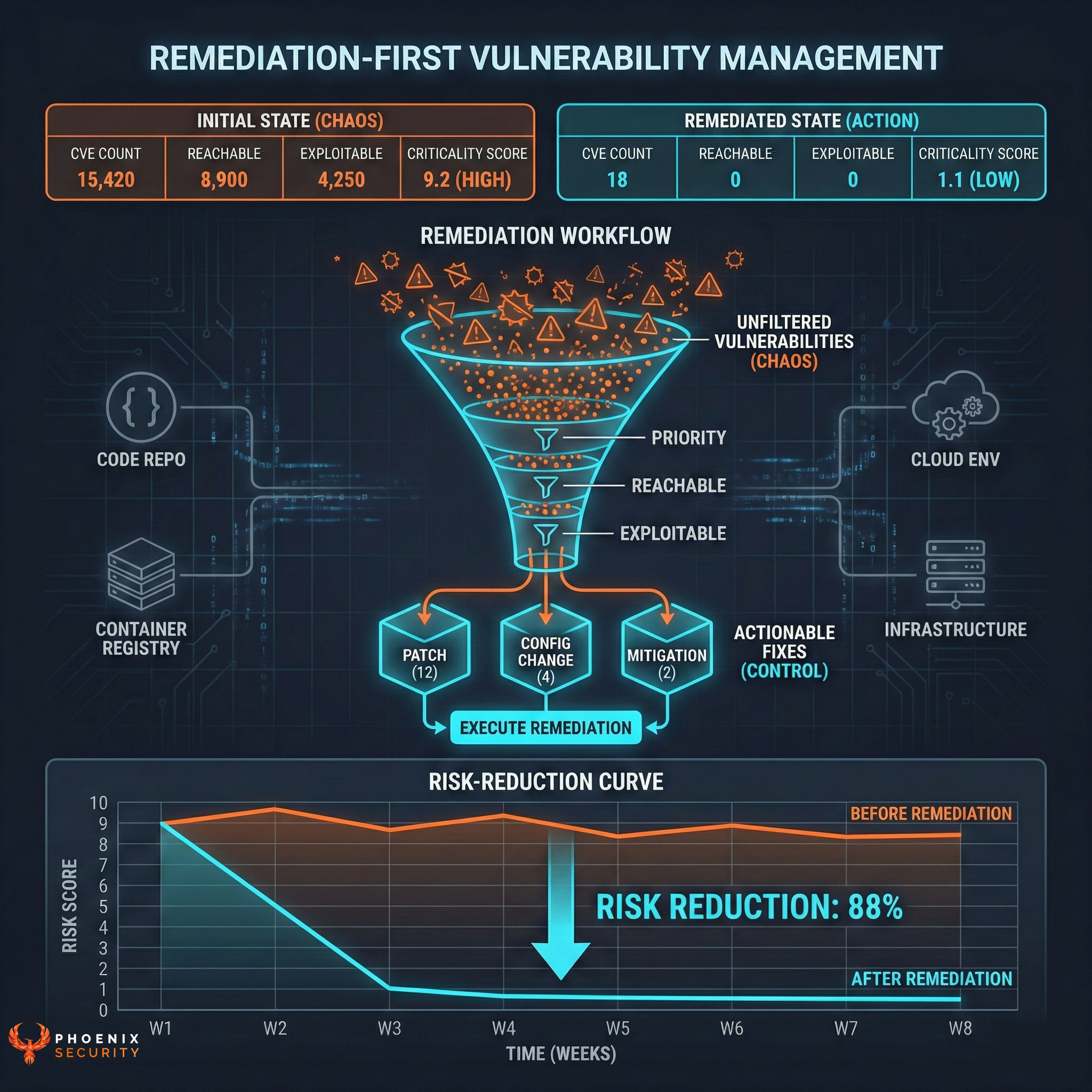

Minimize the vulnerability risk and act on the vulnerabilities that matter most, combining ASPM, EPSS, and reachability analysis.

Organizations often face an overwhelming volume of security alerts, including false positives and duplicate vulnerabilities, which can distract from real threats. Traditional tools may overwhelm engineers with lengthy, misaligned lists that fail to reflect business objectives or the risk tolerance of product owners.

Phoenix Security offers a transformative solution through its Actionable Application Security Posture Management (ASPM), powered by AI-based Contextual Quantitative analysis. This innovative approach correlates runtime data, combines it with EPSS and other threat intelligence, and applies the right risk to code and cloud, delivering a prioritized list of vulnerabilities.

Why do people talk about Phoenix Security ASPM?

• Automated Triage: Phoenix streamlines the triage process using a customizable 4D risk formula, ensuring critical vulnerabilities are addressed promptly by the right teams.

• Actionable Threat Intelligence: Phoenix provides real-time insights into vulnerabilities’ exploitability, leveraging EPS and combining runtime threat intelligence with application security data for precise risk mitigation.

• Contextual Deduplication with reachability analysis: Utilizing canary token-based traceability for network reachability and static and dynamic runtime reachability, Phoenix accurately deduplicates and tracks vulnerabilities within application code and deployment environments, allowing teams to concentrate on genuine threats.

By leveraging Phoenix Security, you not only unravel the potential threats but also take a significant stride in vulnerability management, ensuring your application security remains current and focuses on the key vulnerabilities.