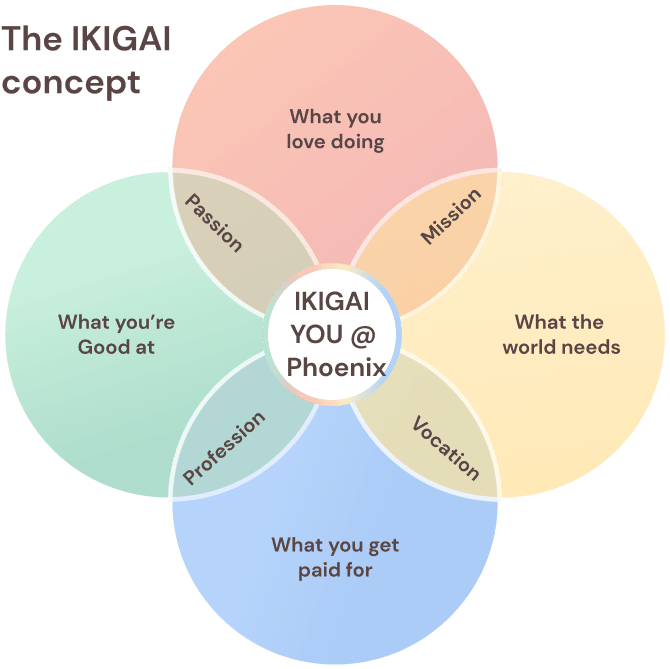

How do you measure and facilitate the best way resolution of vulnerabilities without crashing the spirit and soul of the development team with the dreaded sentence, fix vulnerabilities in X number of days?

Let’s start by clarifying development teams have the will and spirit of writing perfect code and solving vulnerabilities. Businesses need to ship features fast to increase revenue, augment the sales surface, winning more clients.

Those two elements have always been conflicting, and the security requirements (often not at the start of the project) is lacking in the objective of application owners or business.

From this challenge, developers often lack the time and objectives to resolve vulnerabilities and bug fixes sprint by sprint.

So how can this be fixed? In several days, security mandates to fix problems (vulnerabilities, bug fixes, misconfiguration, libraries). The resolution times, often called SLA, are usually not agreed upon in collaboration with CTO and the development team.

This mandate often causes friction and frustration among everyone.

I have been having conversations with different professionals and experts in the field and had more or less argumentative discussions around SLA, SLO and OKr in Vulnerability management, Application and cloud security.

This article will cover the complexity of the landscape and the significant difference between various “updating” strategies and elements to consider when setting SLA, SLO or grouping them.

We will explore how those metrics with a feedback loop between security and development teams can facilitate a conversation and turn the tide in a usually frustrating exchange.

Definitions

Let’s start with definitions of SLA, SLO and what they are:

- A service-level agreement is a commitment between a service provider and a client. Particular aspects of the service – In our specific case, SLA stands for the number of days a particular vulnerability must be fixed.

- A service-level objective is a critical element of a service-level agreement between a service provider and a customer – Similar to SLA but is not an agreement but rather an objective.

- SLI – I will skip it for now

- OKr – Objectives to achieve (specifically in the DevOps team (something like the number of vulnerabilities per spring

| SLI | SLO | SLA | |

| Definition | A quantifiable measure of reliability | A target reliability level objective | A legal contract or agreement that, if breached, will have penalties |

| Example | The number of vulnerabilities should be < 10 for every release | Critical Vulnerabilities will be resolved in 28 days 95% of the time | Public available products will have 0 critical vulnerability upon release critical vulnerability disclosed will be solved in 10 days |

| Who Sets it | Security teams in collaboration with Product Owners | Product owner in partnership with security teams | Business Development, Legal team, IT and Devsecops |

Vulnerability Landscape

The vulnerability landscape in modern organisations is complex; we can categorise the vulnerability types or misconfiguration in several categories. Vulnerabilities in the various categories have quite different behaviour and require different levels of attention.

We can categorise assets in the following categories:

- Application security – Vulnerabilities that concern codes, libraries or similar

- Infrastructure Cloud security-related – vulnerabilities that concern images or similar infrastructure systems running in the cloud

- Cloud security – misconfiguration of cloud systems (Key manager, S3)

- Network security / Cloud security – vulnerability affecting network equipment like WAF, Firewall, routers

- Infrastructure security – Categorized as everything that supports an application to run that is traditionally Server, Endpoints, and similar systems

- Containers vulnerabilities (somewhere in between application container/cloud security with running containers, image stores and the system that composes containers

The approach to measure the security posture and the security health of different elements that compose our approach is quite comprehensive, the picture below gives a good idea.

The resolution time, hence SLAs, is fairly different between assets in the various categories.

Following is an example of the tooling that traditionally detects vulnerabilities in various containers illustrated above.

Fixing landscape

Applying patches and mandating SLA seems straightforward, but in reality, many factors influencing, fixing and resolving vulnerabilities can be a bit of a learning curve/journey.

The reason for such a complex landscape is because the factors that influence fixing systems and resolving vulnerabilities are many:

- System Complexity

- Different Layer of patches

- Testing is required and several teams/clients involved in testing

- Number of groups involved in the fix

- Exposure to clients and criticality of systems (Downtimes allowed)

- Maintenance windows

Moreover, fixing vulnerabilities in the various system should not be delegated to just one team but rather have an objective and measurable target to discuss in the context of risk.

Some of those elements can be automated, but mostly not; every system has different contracts and requirements. Nonetheless, those can be fed as business requirements for SLA and determine the bucket or Categories of the system for SLA/SLO/OKr.

Usually, systems are categorised into

- Critical system – uptime is vital, and windows for updating are tight

- Medium criticality – uptime is essential, but windows for an update are more relaxed

- Low criticality – downtime and update windows are very flexible.

Following several different elements to consider for patching and adjusting the time for SLA, SLO, and writing OKr.

The following is to be taken as a guideline, not as an exhaustive list of topics.

Patching / Infrastructure

- SIMPLE – Patch (easy) upgrade with simple testing, maintained by only one team

- SIMPLE/MEDIUM – Patching a system with some testing requirements maintained by one or two teams

- COMPLEX – Complex system with multiple dependencies and configurations

- VERY COMPLEX – Complex system with various applications and multiple teams maintaining different parts and vast client surface

Cloud

- SIMPLE – updating a system rule in a register, settings in a cloud element (e.g. S3)

- SIMPLE/MEDIUM – Changing the role, IAM rule, Permission rule

- COMPLEX to VERY COMPLEX – Restructuring the architecture of a service, introducing controls, changing access methodologies, changing settings that involve user interaction

Containers

- SIMPLE – library or dependency without significant impact

- MEDIUM – changing a critical library or os that potentially breaks dependencies

- COMPLEX – updating container image with multiple dependencies and different running containers utilising the image

- VERY COMPLEX – updating a container’s image that is used widely across the organisation e.g. Linux, with the deprecation of a function utilized by one or multiple systems

Updating Libraries

- SIMPLE – updating a library without critical dependencies

- MEDIUM – changing a critical library that potentially breaks dependencies on one application

- COMPLEX – Changing a library from minor to major version, with deprecated libraries that require swap of those functions in multiple parts of code

- VERY COMPLEX – similar to complex, but when the number of teams is multiple and distributed

Update Code/ Bug Fixing

- SIMPLE – changing a simple variable, function with a minor regression testing

- MEDIUM – changing a function or a section of code with medium impact in the individual file or limited number

- COMPLEX- updating a major section of the code, changing inputs from one or multiple user perspectives that requires extensive testing

Security Timelines

- Discovery to Declaration to CVE – This timeline is usually the most dangerous and relates to the discovery of vulnerability – commonly in this timeline there is no patch available, and the systems are at risk for the so-called 0 days.

- Disclosure in the wild of vulnerability usually involves the vulnerability being disclosed widely on the web for various reasons, giving the vendor no chance to fix the vulnerability. The resolution time/mitigation time becomes critical.

- CVE Registration – The CVE register acknowledges the vulnerability, and the vulnerability does receive a specific code.

- PoC – Proof Of Concepts made available – usually, the PoC is a piece of code that exploits vulnerabilities in systems.

- Vulnerability identified in network/container/code.

- The vulnerability being worked on by the team – Not all the time. A vulnerability/ patch is straightforward to fix. Sometimes, an update is quite straightforward and requires few updates; others require extensive testing and careful planning

- The vulnerability is being remediated by the team.

- Vulnerability remedy being confirmed (pentest, Security scanner).

Conclusion

Vulnerabilities are a complex matter and there is no one single answer that fits all.

Vulnerability resolutions and considerations around the vulnerabilities complexity of teams needs to be a collaborative process between the security team and the product/development team

Vulnerability prioritization and contextualization become key to free up the security team from deciding what to fix and what not to fix. Security teams can then turn into a more consultative and collaborative approach with the development team helping them succeed in deciding how to fix specific problems vs what to fix or not